There are hundreds of military bases scattered across Afghanistan, from concrete watchtowers, surrounded by razor wire, to massive airbases, fortified with concrete blast walls and watchtowers stretching for miles. Hundreds of thousands of Afghan and foreign soldiers, officers, technicians, cooks, cleaners and generals occupied these bases, along with armoured Humvees, helicopters, gunships, transport aircraft and drones. Most of them were built by the Soviets during their occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s, but they were expanded and modernised by the US and Nato, with billions of dollars paid to mostly US military contractors for maintenance, catering and training.

In the space of a month last summer – nearly twenty years after George W. Bush launched Operation Enduring Freedom – all these bases, large and small, fell to the Taliban as the last US troops prepared to withdraw from the country. In almost every case, the Taliban fighters didn’t have to worry about the fortifications. The Afghan army personnel inside opened the gates, put down their weapons, changed into civilian clothes and went home, demonstrating the monumental failure of yet another foreign invasion of Afghanistan. For the US, it was a remarkable and embarrassing defeat, the worst since the fall of Saigon. It was followed by another fiasco, as Western countries and their allies struggled to evacuate foreign nationals and tens of thousands of Afghans who were trying to flee from the Taliban takeover. The Taliban – essentially a rural insurgency – have neither the manpower nor the need for all these bases. They stripped them of weapons, vehicles and equipment, and abandoned them. Today they are reminders of the hubris of a failed empire, and gradually the people who live in their shadow are demolishing them.

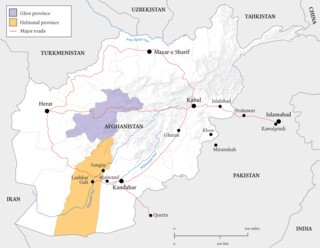

In the town of Sangin in Helmand province, a man was rebuilding his house on the outskirts of one such base. ‘They evicted me and my family, destroyed my house to build this base,’ he said, his hands white with dust. His sons and nephews were shifting rubble while a cousin was mixing mud and straw to mould into building blocks. Above them were the remains of Forward Operating Base Jackson, machine gun nests still protruding from the rocks. American, British and Afghan forces based in this fortress on a hill overlooking Sangin and the desert beyond had repeatedly tried and failed to drive the Taliban away from the town, which controls the road to Kandahar and is a major hub for the opium trade. Thousands of soldiers, both army and Taliban, were killed in the fighting in Helmand, along with thousands of Afghan civilians and five hundred American and British soldiers. The British, who took over the base in 2006 and left in 2010, lost more men in Sangin than anywhere else in Afghanistan, often to roadside IEDs or explosives planted in orchards and fields.

Inside the base the ground was littered with empty ammunition crates, discarded uniforms, flak jackets and yellow plastic jerrycans. A watchtower had been constructed with wooden planks, sandbags and HESCO barriers – collapsible mesh boxes with heavy-duty fabric liners, filled with dirt and gravel. These portable structures are ubiquitous in Afghanistan, remnants of America’s failed war. Invented by a British ex-coal miner in the late 1980s, HESCO barriers were originally designed for flood control and to prevent erosion. Millions of them were used to barricade government buildings, checkpoints and military installations, crumbling as the war dragged on, their gravel spilling out only for new ones to be positioned on top of them. Now the HESCOs are being repurposed, used as fences for animal pens and chicken coops, or flattened to make doors for mud-built shops. Or for a watchtower like this, manned by three Taliban sentries, with the white Taliban – and now Afghan – flag fluttering above them in the breeze.

The major lived in a small apartment in one of Kabul’s rapidly expanding suburbs. Few of his neighbours knew that he had served in the Afghan army for nearly fifteen years, but he still feared for his family’s safety. He had begun his career in 2006, joining the newly established National Military Academy of Afghanistan, set up after Presidents Bush and Karzai signed an agreement that Washington would ‘help organise, train, equip and sustain Afghan security forces as Afghanistan develops the capacity to undertake this responsibility’. Staffed by Turkish and American instructors, the academy churned out large numbers of junior officers, in the hope that this would allow the Afghan army to overcome the suddenly resurgent Taliban – suicide attacks had quintupled between 2005 and 2006. Eighteen months later he graduated with honours and served in Afghanistan’s southern and western provinces along the border with Iran and Turkmenistan, before ending up in a district of Ghor province, west of Kabul, dominated by high cliffs and deep valleys. Both the Russians and the Americans had failed to conquer the area, and during their first period in government, between 1996 and 2001, even the Taliban had never fully controlled it.

When Nato’s combat mission in Afghanistan came to an end in 2014, Afghan army units lost most of the close air support they had enjoyed, and the Taliban quickly took over most of Ghor. The major’s base below a mountain ridge was soon surrounded. Rations began to run out. Supply helicopters couldn’t land because of the difficult terrain and members of the unit got by on a bowl of boiled rice a day. ‘We fought with all the weapons we had,’ the major said. ‘Even the unit’s cook carried a gun and fought alongside the soldiers. But we were running out of ammunition. Thirteen men had been killed and more than a third were injured. We were becoming desperate. We decided that we should either abandon the post, and try to fight our way to the top of the mountain to be picked up by helicopter, or surrender, because we had lost the energy to fight.’ Then, after a month under siege, the men got news: the government in Kabul had dispatched a special forces team to come to their aid. A unit of just ten commandos was dropped three kilometres behind the Taliban lines. ‘Those ten commandos, they traded their lives for us,’ the major said. ‘For two days and a night they fought their way from one valley to another to come and rescue us. That was when I realised that we could defend our country by ourselves. We didn’t need foreign forces, just good commanders and co-ordination.’

He was a proud Afghan soldier, proud of his army’s achievements, proud of the changes he had seen take place in Afghan society, proud that he had female colleagues at the military academy. His wife and sisters had government jobs – jobs they still held under the Taliban – and he was hopeful that his children would get a good education and a better future. If there was anyone to thank for Afghanistan’s normalisation, though, it wasn’t the Americans. He felt that the US had used men like him to fight its own larger war against Islam. The Americans ‘killed a lot of Muslims under the pretext that they were Taliban’, he said, before betraying the cause they had purported to defend by signing a deal with the Taliban. Trump’s Doha agreement of February 2020, which the Afghan government wasn’t even invited to discuss, promised a full withdrawal of US troops if the Taliban met certain conditions. This decision could have been overturned by his successor – but instead Biden merely extended the deadline for withdrawal by three months, clearing the way for the Taliban takeover to begin.

In early 2021, with the inevitable offensive looming, the major was put in command of a battalion that helped to defend four provinces to the north and east of Kabul. The Taliban attacked his positions several times over the summer, but his men were prepared. They had plenty of arms and ammunition, and his base on a ridge overlooking a major highway was well defended. Even as the Taliban captured one provincial capital after another in the first weeks of August he held firm, until a commander from a neighbouring battalion told him that the governor of Nangarhar, one of the provinces under his remit, was about to surrender to the Taliban. The rumour was confirmed at 5 a.m. the next day when pictures from inside the governor’s office in Jalalabad appeared on the Taliban’s social media channels. ‘I still couldn’t believe it. I called the corps headquarters and my senior commander was crying,’ he said. ‘There was nothing I could do. Our superiors had surrendered, and these were orders.’ He was asked to return to headquarters with his battalion and their weapons and ammunition. For the next few hours his men refused to move, until he persuaded them that to be the last force standing would be suicide. There was no more resistance, and on 15 August Kabul came under Taliban control.

I asked the major why the army hadn’t rebelled, why the senior officers hadn’t ignored civilian orders. He replied by citing the precedent of Mohammad Najibullah, the last communist leader of Afghanistan, who continued fighting the mujahideen after the Soviet troops left in 1989. Nearly sixty thousand people died in that period of the civil war and the country’s infrastructure was devastated. ‘Now times are different,’ the major said. ‘People are more educated and they hate war. We didn’t want to destroy all the developments of the last twenty years, we didn’t want to kill more people.’ The withdrawal of Soviet military support had spelled the end for Najibullah’s government. Now, just as surely, the withdrawal of the Americans could only lead to a second Taliban takeover. Under first Hamid Karzai and then Ashraf Ghani, the Afghan government was transparently a US client, just as Najibullah’s government had been a Soviet one. Once they were abandoned by their sponsors, there was no way either could survive. This time it would be better for the government to collapse quickly, without blood. ‘I’m disappointed every time I see a Talib in the streets,’ the major said. ‘I know they gave us all amnesty, but we will never be as free and modern as we were. I had female classmates and some even became commanders. Now I feel like all this progress has turned to dust.’ ‘Watan raft, watan raft,’ he said: ‘The country is gone, the country is gone.’

The Taliban’s roots lie in the civil wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s. As part of its proxy war against the Soviets, the US provided money and support to a jihadist movement that strongly resisted communist rule. Saudi Arabia joined the US in financing the mujahideen, and training and equipment were supplied by Pakistan’s ISI. After Najibullah’s fall in 1992 and the disappearance of a common enemy, Afghanistan’s armed factions began a vicious civil war, killing thousands of civilians and reducing much of Kabul to rubble. The warlords struck alliances, betrayed one another, and then struck new alliances while their men pillaged. The country was divided up between the warring factions, and petty commanders levied tolls, imposed taxes and terrorised a population already brutalised by war.

At the time, Mawlawi Burjan, who came from a poor Pashtun village in south-east Afghanistan, was studying in a madrasa near the Pakistani city of Quetta. To get there from his village he had to pass through Kandahar and cross a dozen or more checkpoints. ‘There was no such thing as the Taliban movement back then, and travelling was becoming really hard, sometimes even impossible,’ Burjan told me when I met him in Kabul. ‘We would pick a route through villages in the mountains or cross the desert to avoid the main roads. No young boy could travel on the Kandahar road, because these men were ruthless. Women were harassed, sometimes kidnapped and raped. They would force people to pay a lot of money, and if someone didn’t pay they would be tortured.’ In 1993, a group of Pashtuns from the south and south-east, appalled by the actions of some of the former mujahideen, decided to restore some kind of order. The group coalesced around a reclusive mullah called Omar, a veteran fighter who had lost an eye to shrapnel during the war against the Soviets. To differentiate themselves from the warlords who had sullied the name of the mujahideen, Mullah Omar’s group called itself the Taliban, the Pashtun plural for the Arabic word talib, ‘student’, since they had all been students or teachers at madrasas in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The founding legend of the movement speaks of those few pious men, armed with a few rifles, taking on much stronger militias to avenge the local population. At one point they are said to have hanged a warlord commander from the gun barrel of a tank, in order to save a young boy and two girls from rape. While a widespread yearning for safety and stability played a role in attracting people to the new group, it was the support of the powerful trucking mafia – weary of the exorbitant tolls imposed by the warlords whose checkpoints littered the roads and who sometimes looted and hijacked their trucks – that established the Taliban as a force to be reckoned with. Soon they had secured the roads between Kandahar and the border with Pakistan, before taking over the border crossing and seizing a large arms depot.

At this point the Taliban won the backing of Pakistan’s intelligence services. The ISI had come to accept that their preferred candidate, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, drug trafficker and leader of the Hezb-e-Islami militia, was incapable of taking Kabul, let alone the rest of Afghanistan. They believed, mistakenly, that since it was a small and nascent movement, the Taliban would do Pakistan’s bidding. Helped by funding from the ISI and the trucking mafia, the Taliban captured Kandahar, Afghanistan’s second biggest city, along with significant quantities of arms and military hardware. What had been a band of Robin Hood-like vigilantes was now a full militia armed with tanks, helicopters and even a few MiG fighters. A few months later Burjan was among the thousands of young madrasa students who flocked to join it. Former mujahideen commanders and tribal elders, acknowledging the Taliban’s growing power, started to pledge allegiance. Money came in from the UAE and Saudi Arabia, and in 1996 the Taliban took over Kabul. By 1998, they controlled most of Afghanistan, apart from some areas in the north-east, where the Northern Alliance held out.

‘Our country was more peaceful,’ Burjan said. ‘Members of my family were able to work in the market without any fear. With the peace the Taliban brought, people could go to work and build a small business without anyone interfering. There was no discrimination: you could find a job anywhere.’ The price for that peace was the imposition of the Taliban ethical code – a combination of the strict Sunni Hanafi legal code and Pashtun tribal ethics – on the population, as the group pledged to purge ‘un-Islamic’ and ‘infidel’ thoughts and behaviour from the cities it had conquered. Burjan welcomed this. Women were required to wear the burqa and forbidden from holding public jobs, wearing perfume or looking at strangers.

For a few years, Burjan assisted a Taliban commander, before eventually being assigned more important security tasks that required him to travel across Afghanistan. But throughout his years of service he still had to return regularly to his home village to work with his brother making and selling bricks. ‘The Taliban movement was poor,’ Burjan said. ‘We were all working to support ourselves and our families. Even the movement itself was funded with aid from local businessmen and Islamic countries. Some of that aid we would distribute to the local people.’ The majority of the Taliban were drawn from the poorer parts of Pashtun society, the semi-nomadic clans. Many were war orphans, or children of the landless and impoverished sharecroppers who had been displaced by the fighting and were scavenging for a living in refugee camps and shanty towns.

The Taliban’s military victories led Mullah Omar to proclaim that he was carrying out a divine task, not only saving Afghanistan from the warlords but establishing a ‘true’ Islamic state. He appeared before a large crowd of the faithful in Kandahar wearing Afghanistan’s most sacred relic, the cloak of the Prophet or Kherqa-ye Sharif, thus giving himself mystical status. Gradually Omar marginalised the moderates within the movement. The influence of Osama bin Laden and his fellow Arab jihadists, whose presence in Afghanistan provided a major source of income, began to be felt: until then, the Taliban had taken their inspiration from the teachings of the Deobandis of the subcontinent rather than the Muslim Brotherhood or the Wahabbis of the Middle East, but elements of Salafi-jihadist doctrine soon started to seep in.

Then came the American invasion. On the night of 12 November 2001, the Taliban fled Kabul en masse. Burjan took his family to his father-in-law’s house on the outskirts of the city and the next morning he and his wife and children drove out of town. All around him were the relics of defeat: guns and crates of ammunitions abandoned by the fleeing Taliban. He was angry to see people looting the weapons, celebrating the end of Taliban rule before the US-backed Northern Alliance forces entered the city. The roads ahead were blocked so he had to take a circuitous route through the mountains. When he reached Ghazni, south of Kabul, he found that the Taliban had retreated from there too, but because he was travelling with his wife and children he avoided questioning by US soldiers and eventually made it to his village in the south.

Sher Agha was not so lucky. He worked in the Taliban’s interior ministry, and when Kabul fell he feared the worst. He took refuge in his brother’s shop while he tried to find a way to slip out of the city. One night he woke up to find the shop surrounded by Afghan soldiers. They dragged him out, handcuffed and blindfolded, and took him to a police station manned by Afghans and Americans in military fatigues. He was hung by his wrists from the ceiling, whipped with cables, punched and kicked. The torture went on for several hours. Eventually he was put in a cell with fifteen other men – all of them, like him, former officials in the Taliban administration. After any invasion, the occupying power has a decision to make: what to do with the petty bureaucrats, the ordinary employees of the government it has deposed. Punish them, or let them go? As is often the case, the US and its allies in the Northern Alliance seemed to vacillate on the question, and in a sudden reversal Sher Agha found himself in a taxi being driven back to his brother’s shop. There, to his surprise, his captors untied him, gave him some food and apologised for their behaviour.

So, like Mawlawi Burjan, he set off for home, in his case the mountainous region of Khost in eastern Afghanistan. Over the next few months he got in touch with other former Taliban, trying to revive old networks and bring in new recruits. ‘We sold everything we owned, so we could return to the field and start the jihad,’ Sher Agha said. But his first military action was nearly a flop. His plan was to target American and Nato bases near the Jalalabad road with some old rockets he had procured. But first he needed military maps. ‘We contacted some people in Kabul and they couldn’t find us maps. Another brother found us an engineers’ map he had bought for 500 Afghanis but it wasn’t accurate enough for this kind of job.’ So he and a couple of friends set up camp on a hill overlooking the bases and decided to make the best of it. ‘While we were preparing the rockets, one of the brothers didn’t fix the launchers properly. I told my men this is not good, but they weren’t professional at all, so I thought let it be.’

‘Some of the rockets worked,’ he said. ‘Others missed and hit the mountains. One flew straight up and exploded, covering us with shrapnel.’ Helicopters were sent out to hunt the men down. But they got safely back to base. The next morning they turned on the radio to learn from the BBC that some of the rockets had hit their targets. ‘The BBC also announced the name of some organisation that was behind the attack,’ he remembered with amusement. ‘But there was no organisation, it was just three people.’ Eventually, government soldiers found their base – but Sher Agha was able to pay them off. ‘The person who took the bribe from us is still alive,’ he said. ‘He’s studying religion now.’

Sher Agha soon expanded his network. From Khost, he crossed the Pakistani border to Miran Shah in North Waziristan, where he built a training camp. ‘We used the training camps to educate and drill new recruits, and then dispatched them to different provinces,’ he said. ‘We also experimented with new techniques and new kind of explosives like barrel mines, manufacturing them ourselves.’ At first they had no success against US military technology, but then they started adapting guerrilla techniques they had mastered while fighting the Russians. They found they could take gunpowder from old Soviet ammunition and mix it with fertiliser and other chemicals to make IEDs powerful enough to destroy American armour.

For Sher Agha, the fight was personal. His wife and children moved from place to place with him. One of his brothers was detained three times. Another brother was killed in a night raid on his house. He and his men took all due precautions, moving between safe houses and never using phones, relying instead on messengers. He pointed at a young man in military jacket, cap and wrap-around sunglasses, carrying a machine gun with night vision scopes. ‘He is my nephew,’ Sher Agha said. ‘He was a messenger and spent time in jail. In the twenty years of fighting he lost many of his friends and relatives. We believed that their blood and sacrifice would bring us victory. That is why after twenty years we were able to reclaim our Islamic state.’ I was talking to him in a garden at the top of the Wazir Akbar Khan hill overlooking Kabul, with several of his cousins, nephews and members of his clan gathered around him, all of them carrying brand-new American guns and gadgets. After the Taliban took the city back last summer, Sher Agha was appointed commander, and he is still committed to the city’s defence.

However you look at the last twenty years, it’s hard to deny that the US bears much of the responsibility for its own failure. The transitional government it installed in June 2002 – headed by Karzai, who was viewed as reliable by Washington and the CIA – was a cobbling together of prominent Pashtuns and former warlords, the very people who in destroying so much of Afghanistan in the civil war of the early 1990s had brought about the Taliban’s rise. Those who had assisted the US invasion, whatever their backgrounds, were given senior government positions and immunity from prosecution. Karzai’s three vice presidents had all been commanders in the Northern Alliance. In Afghanistan as in Iraq, the US very quickly toppled the previous regime but failed to build any viable institutions. Instead they shared out rewards indiscriminately to establish a system of patron-client networks. The new elite – generals, ministers and provincial governors – proceeded to loot and embezzle the international aid that poured into the country. There were ghost schools, ghost roads, ghost hospitals: projects funded by the international community that existed only on paper.

Everyone blamed everyone else. The US accused the Afghan government of corruption and incompetence – never mind that this was a government of its own making. For their part, Afghan politicians, not quite as pliant as Washington might have wished, accused the Americans of arrogance and insensitivity to Afghan grievances. As the US repeatedly killed civilians in night raids and drone attacks, there was plenty to be aggrieved about. But twenty years later there is one thing Afghans and Americans agree on: they both think it is Pakistan that has enabled the Taliban to return to power. Ever since the invasion, they believe, Pakistan has been playing a double game, supporting the Nato and American war effort by day while quietly assisting the Taliban by night.

‘To understand Afghanistan you have to start in Islamabad,’ a former ISI officer told me. ‘Everything began here forty years ago, and I was a major part of it all.’ He said that his role in Afghanistan began with the Soviet invasion in 1979. At the time, during the regime of General Zia, he was a junior intelligence officer tasked with helping to train, fund and supply the mujahideen. At first, he said, the initiative had been Zia’s alone – but Pakistan gladly took up the offer to funnel US and Saudi aid to the fighters in Afghanistan. ‘We welcomed their support then,’ the officer said. ‘We needed their weapons and their money. But we didn’t allow the Americans to communicate with Afghan mujahideen directly. Because we wanted to keep control in our hands. This was our war.’ Gleefully, he recounted the benefits Pakistan reaped from that war. Co-operating with the US rescued the country from the diplomatic isolation it had suffered since the execution of Zia’s predecessor, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. It was able to buy squadrons of American F-16s and build a formidable air force. And – most important of all – it became a nuclear power. ‘Because the Americans needed us they couldn’t do anything to stop our nuclear programme.’

As far as this officer was concerned, ‘Pakistan’s war’ in Afghanistan had been a total success. By contrast, the US invasion brought nothing but trouble. ‘America was here for twenty years and what did we get? Thirty thousand dead Pakistanis, including ten thousand security personnel, among them a lieutenant-general. We never lost a lieutenant-general in three wars with India. Suicide bombers, four hundred drone attacks, midnight raids, the bombings of weddings and hospitals, and the killing of the innocent in both countries. Collapse of the economy and a sense of insecurity in Pakistan. This is what we got in twenty years of fighting the American wars.’ But he failed to mention any of the benefits that ensured Pakistan’s continued assistance after 2001: the latest American arms, sanctions lifted a billion dollars of foreign debt written off.

Twenty or so kilometres south of Islamabad, in the city of Rawalpindi, seat of the GHQ, the sanctum sanctorum of the Pakistani army, I met a former high-ranking army officer. From the mid-1980s onwards he too had been one of the architects of Pakistan’s Afghan strategy, and he had a close working relationship with the Taliban, both before and after 2001. In the immediate aftermath of the US invasion, he said, Pakistan had complied with American interests by giving the Taliban ‘no shelter’. But gradually it became clear that this policy had to change. ‘There was a general feeling of humiliation in the army and a belief that Musharraf was doing too much for the Americans.’ As they saw it, the Americans would one day leave, but there was no arguing with geography: Afghanistan would always be Pakistan’s problem, and this was its war too. It wasn’t true, he said, that Pakistan had continued to provide the Taliban with support – but the relationship was complicated.

The complications have to do with the Durand Line, drawn up in 1893 after the Second Anglo-Afghan War to demarcate the border between British India and the emirate of Afghanistan. Now it forms the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. But it also cuts through the tribal Pashtun region that straddles the border. Ever since Pakistan’s inception in 1947, successive Afghan governments – monarchical, republican, communist, democratic – have refused to recognise the line, claiming that the region and especially the city of Peshawar are part of ‘historical Afghanistan’. Afghan leaders repeatedly supported separatist insurgencies on the Pakistani side of the border calling for the establishment of a ‘Pashtunistan’, that would unite Pashtuns in both countries.

The border dispute attracted the attention of India. It is in India’s interest for trouble to continue on Pakistan’s western border, and over the last ten years it has tried to form close ties with the government in Kabul, providing training for its soldiers and pouring money into big construction projects: the new Afghan parliament building, the Afghan-India Friendship Dam in Herat province, mines, power plants, roads. For India, Afghan and Pashtun nationalism is a force to be cultivated; for Pakistan, India’s sponsorship of it is a danger. One advantage of the Taliban is that in insisting on Islamic identity above all else it diminishes the force of nationalism.

The relationship between Pakistan and the Taliban isn’t as simple as that between master and client. It’s true that the Taliban has long been dependent on safe havens in Pakistan: almost every Talib I have met in Afghanistan over the past two decades has told me of their regular trips between the two countries. After 2001, the Taliban’s central governing body, the Leadership Council, was based in Quetta, and some Taliban-affiliated groups, especially the Haqqani network, received military training in Pakistan. But, like all Afghans, they did not take kindly to foreigners ordering them around, even fellow Muslims. Taliban commanders were persecuted, harassed and sometimes imprisoned if the ISI considered them too independent. Sher Agha said that even in their safe haven in North Waziristan he and his men had to be very careful. ‘We were hiding from the Pakistani government as well as the Afghan government, and it took us three or four nights to travel between the two countries.’

The former Pakistani army officer stressed that over the last twenty years the Taliban was quietly pursuing its own, very effective strategy: its continued small-scale military actions were a way of wearing the Americans down, ensuring eventual financial and moral fatigue. In the meantime it was expanding its ranks and solidifying its command. When the Taliban launched its operation to retake Afghanistan last year, even the Pakistani army was surprised at the speed of its gains. This success, the officer suggested, could be attributed to the Taliban’s carefully considered methods. ‘The Afghan army was still well equipped and could fight,’ he said. ‘But it collapsed because its command structure was weak and all decisions were centralised. The Taliban, on the other hand, divided the frontline sectors between different commanders, and they launched multiple attacks all over the country, forcing the Afghan army and their special forces to fight on multiple fronts without giving them a chance to recuperate.’ Once they had surrounded a unit, the Taliban would send a jirga, a council of elders, to negotiate with the army commanders. ‘The choices then for field commanders, who were logistically isolated, were about saving their lives.’ The Taliban’s victory, the officer felt, could be attributed as much to their negotiating skills as to their fighting strength.

Kandahar, the birthplace of the Taliban, is an oasis town, watered by the Arghandab river and its tributaries. It sits on the ancient trade routes connecting the Sindh and the Indus Valley to Herat, Persia and Central Asia. It was a contested frontier trading post between the Mughal and Safavid empires, and as they entered their decline in the mid-18th century it became the seat of a new kingdom under Ahmad Shah Durrani, who united the Afghan tribes to establish an empire that at its height stretched from eastern Iran through Turkmenistan to north-west India, encompassing all of present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan as well as Jammu and Kashmir. Durrani, whose octagonal tomb in the centre of Kandahar is one of the most visited shrines in the country, is known as the father of modern Afghanistan.

‘The history of Kandahar is different from other cities,’ a Taliban commander told me. ‘If you capture Kandahar you capture Afghanistan.’ He was speaking from experience: he led the force that took the city on 13 August last year. ‘Although people say the army surrendered without much of a fight,’ he said, ‘here in Kandahar the fighting was hard and we lost many good men.’ Their first target was the prison. ‘Most of the inmates were our brothers,’ he said, and as soon as they were freed they joined his men. He doesn’t remember exactly when he started fighting government and American forces, maybe a year and a half after the US invasion began. ‘We started with very small attacks, ambushing convoys and planting IEDs. It took us a year or a bit more to organise our fronts, and gather our men. We started recruiting from the villages and the towns. Even when the Americans and the Canadians came here they couldn’t defeat us, because we had the support of the people, and the resistance of the people of Kandahar is legendary. We made our nests in their houses and villages.’

By 2009, he said, ‘the fighting was so intense that sometimes we were separated by fifty or a hundred metres from the enemy. We didn’t fight to make money. Our aim was to establish that we are all from this region. People know my family, my ancestors. We were not strangers to them. We have already showed the world that we can defeat and humiliate Nato, and those Afghans who came with them were defeated too. They can’t come back any more.’

What the commander didn’t say was that it took the Taliban longer to capture the south, their original habitat, than anywhere else in Afghanistan. It was here that they lost the most men – essentially because some of the tribes in the region fought against them, not with them. According to one Afghan journalist I spoke to, in Lashkar Gah, the capital of Helmand province just west of Kandahar, even after the army and police surrendered tribal fighters continued to resist the Taliban, until finally they ran out of ammunition and were evacuated.

On Kandahar’s western edge, the narrow traffic-filled roads give way to fields, vineyards and compounds behind high mud walls. There I joined a wealthy landowner as he strolled through his orchard of mulberry, pomegranate and apple trees. Skipping briskly over irrigation ditches, he showed me tree trunks riddled with bullets and a crater left by a mortar shell. He nodded towards one end of the orchard: ‘Over there is the Kandahar army base, and the prison.’ Then he pointed in the other direction: that was where the Taliban came from, he said. His orchard lay in between: ‘For 25 days we were in the crossfire, and we couldn’t leave the house to water the trees.’ To make his point he picked up a pomegranate and said: ‘Look how small it is. At this time of year it should be much bigger.’

The Pashtuns are divided roughly into two confederations of tribes, the Durrani and the Ghelzai. Most of the Taliban’s early leaders came from the poorer, more nomadic Ghelzai tribes, while some of the Durrani clans are Afghanistan’s closest approach to aristocracy: the source of the country’s kings. Hamid Karzai is khan of the Popalzai, a Durrani clan. The landowner was also a Durrani khan. He showed me some photographs in his study: men in karakul hats, with swords and long coats – his great-grandfather and great uncles. In one picture they were standing around King Amanullah, a moderniser who in the 1920s had tried to replicate Atatürk’s reforms. In proper aristocratic fashion, the khan said he was going to his home village of Maiwand that evening for a partridge hunt, and I could join him if I wanted.

Maiwand is in the middle of a large opium cultivation area, and desert routes connect it to the major trafficking centres on Afghanistan’s southern border with Pakistani Balochistan. Arriving after dark with the khan, his playboy son and his son’s retinue of city friends, I was offered a tour of the place by a young villager called Gul Jan. He took me to the edge of a cornfield before deciding that there might be snakes and scorpions there, and leading me instead towards a domed shrine at the other end of the village. Inside was a small room with whitewashed walls, at its centre a tomb covered in a velvet sheet embroidered with Arabic verses. Two green pillows lay on the sheet, at the head and foot, and the young man kissed each in turn, before kissing the walls and then the door as he led us out again, walking backwards. Whose tomb it was I wasn’t told. Gul said he came here to get the blessing of the shrine before making a journey across the Balochistan desert. He was an opium smuggler and hired gun, and needed all the blessings he could get.

Business was good these days, and the job was simple and based on trust. He said once a deal was finalised between buyers and sellers, smugglers would be hired to deliver the merchandise. They travelled in Land Cruisers, in teams of five, delivering up to fifty kilos of refined opium per trip. The driver was paid 20,000 Pakistani rupees (about £80), while he and the other gunmen got 5000 each, a fortune for a young man like him. They used GPS trackers to find the drop point. ‘I was supposed to get married this weekend,’ Gul said. ‘But I postponed the wedding because an Iranian merchant I had worked with a few times before had a big job for me next week, delivering opium to Iran.’ He said the journey would be risky. As well as the danger of firefights with Pakistani or Iranian security, there was the risk of being mistaken for Taliban and targeted by US drones. But things had improved to some extent since the American withdrawal: he and other smugglers now had free rein to drive across the Afghan section of the desert. Apart from possible clashes with other smugglers, or bandits, the real danger only started after they crossed the Iranian border.

On Maiwand’s main street stand the ruins of the district government building, destroyed during last year’s Taliban offensive. On the other side of the road, tucked behind fruit stalls, butchers and shops selling pots and plastic utensils, are a series of markets dedicated to a particular trade: the tailors’ market, the fuel market with its large oil drums, the animal market with its chickens and sheep, and the Teryak market, where opium and heroin are bought and sold. Small mud-built shops surround a central square the size of a football pitch. Gul took me to shops where men were crouched in front of scales, surrounded by sacks of dried and processed opium. The buyers mainly came from Iran and Pakistan, Gul said, but a few were from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and beyond. The deal would be struck in one of these tiny shops, and the merchandise dropped across the border a few days later. Since the Taliban takeover, the southern drug routes had become even more important for business. The trade northwards – from Mazar-i-Sharif across the Amu Darya river into Central Asia, Russia and Europe – had collapsed when the warlords and army generals who controlled the route and oversaw the smuggling all fled the country.

In April, the Taliban issued an edict banning the cultivation of opium from next season onwards. Gul believes that if this is implemented it will lead to revolt. ‘Everyone here works with opium: the farmers, the shopkeepers and the smugglers. How will people live?’ As we drove through the desert later that morning with the khan and his entourage we passed field after field of opium. At the edge of each one were two or three large solar panels, operating water pumps in wells dug deep into the desert soil to reach the dwindling aquifers. New strains of seed allow farmers to have three opium harvests a year, which makes the supply of groundwater a serious concern. The khan said that he had recently had to resolve a dispute between a Qari, or low-level cleric, who owned an opium field, and his sharecropper, a local Taliban commander. The Qari was an entrepreneur: rather than sell raw opium to be smuggled into Iran or Pakistan, he had built his own heroin factory and was complaining that the Talib hadn’t supplied the promised amount of opium.

We drove on through the desert and up and down hills strewn with boulders before descending into a dry riverbed that ran between two high ridges. ‘This was the Taliban highway,’ the khan said. ‘Their convoys travelled through this valley all the way to Helmand to avoid detection.’ He knew this desert well from his days fighting with the mujahideen in the 1980s. The communists had incensed landowners like him when they confiscated large swathes of land to distribute among the peasantry. The mujahideen faction he joined, dominated by traditionalist religious families and monarchists, was too small and ineffective to make a difference, especially since the bulk of US/Saudi support funnelled through the ISI went to the more radical jihadi Islamists. So what happened to the land? I asked. ‘After the Russians left we took it all back from the peasants.’

Maiwand occupies a special place in the Afghan national narrative as the site of a famous victory over the British in the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Every regime has celebrated the battle: monarchs, communists, mujahideen and Taliban. Schools and streets are named after it and the legend of Malalai, the woman who urged the men to fight (one story portrays her as leading a charge), has inspired generations of Afghan women. The cemetery containing the martyrs of the battle of Maiwand is a national monument. Beyond the graves of the 19th-century warriors who fell fighting the British, rows and rows of new graves have been added, for those who died fighting American and Nato forces in the 21st century. Each is marked by a marble stone: ‘X was martyred fighting the infidels.’ By burying their dead here, the Taliban have incorporated their own story into the national Afghan narrative, portraying themselves as not only a religious organisation but a national resistance movement, an image they were particularly keen to project in the years leading up to their second takeover of Kabul. By appealing to the Afghan sense of honour and cultivating history and religion, they have succeeded in attracting support not only from other Pashtun tribes and clans but from ethnic minorities that have traditionally been opposed to them.

I asked the khan if he thought the Taliban could bring peace to the country. No chance, he said. ‘We need people who know how to use computers. We need engineers and doctors. I don’t want a group of mullahs who are ignorant in their own religion. Do you know why there are no schools even for boys in the village? Because they don’t want the children to be educated. They need them for two things: farming and fighting.’

Early on 26 August last year, Shahnaz and a friend took a car from Herat to Kabul, a thirteen-hour drive, wearing burqas to conceal their identities. The previous day, US-based activists had told them that they were on a high-priority evacuation list, and that their chartered flight was leaving at 7 p.m. that evening. Shahnaz fretted and urged the driver to go faster, but the streets to the airport were jammed and they had to negotiate multiple Taliban checkpoints. By this time, thousands of people were thronging the airport, climbing the fences to get on one of the evacuation flights. If America’s war had ended in a humiliating defeat, the ensuing evacuation was an unmitigated fiasco. Families camped out for days, wading through ditches to reach the runway. There were harrowing images of young men running behind a taxiing military cargo plane, hanging onto its wings and tumbling to their deaths as it took off. Those who could afford it bribed their way onto a flight, while NGOs and embassies evacuated their dogs.

By 5 p.m., Shahnaz was still a couple of kilometres away from the airport and thought she would never make it. Then she heard an explosion, then another explosion followed by the sound of gunfire. The Afghan franchise of IS claimed responsibility for the suicide attack that killed more than a hundred Afghans and 13 Americans. ‘I was really scared,’ Shahnaz said. ‘We didn’t know anyone in Kabul.’ She and her friend didn’t know if they would still be evacuated. The plane chartered by the activists had left right after the bombs went off, and there was no word of another flight. They decided to wait and see, but both were strangers in the city and had no friends or relatives there. They found a hotel near the airport and checked in for a few nights – until a group of Taliban fighters arrived and began interrogating the staff. When they found out that Shahnaz and her friend were staying there alone, they demanded to know why. Her relatives in Herat told her to leave the hotel immediately. They gave her the address of a distant acquaintance who lived not far from the airport and she spent nearly three weeks there waiting for a new flight, listening to the military planes roaring as they took off. The US-based activists rang her every day, promising to keep trying to get them out, but she felt trapped. Eventually she and her friend gave up and headed back to Herat. ‘We thought that at least in Herat we have family and friends. There are many places to hide. In Kabul we were vulnerable.’

Shahnaz was five when the Taliban came to power in 1996. She spent her early childhood largely indoors in a small house in a back street in Herat. She attended an underground community school, where her mother and other female relatives taught girls to read and write. At the time, the word ‘Taliban’ was used by grown-ups to frighten the children. She doesn’t remember much of the war that began in October 2001, but vividly recalled the way her life changed when the Taliban fled the city. Her mother packed away the burqa and went back to wearing the traditional headscarf, long coat and Iranian-style flowery chador. After finishing high school, Shahnaz went to study languages and literature at Herat University. She graduated and became a teacher herself. She formed a women’s association, organised seminars, and worked with NGOs to distribute aid and provide work and microfinance loans for households headed by women. When she was 23, she led a team of monitors in the presidential elections. Early last year she enrolled in a masters degree in international relations. Shahnaz didn’t have any illusions about the limits on her freedom. Both religious and social restrictions surrounded her, and stipulated what was permissible.

‘No one in my family, not even my own father, gave me any support,’ she said. ‘When you start working in the public sphere, alone, men look at you like hungry wolves seeking an opportunity.’ Herat is a wealthy city, dominated by a handful of powerful men who amassed fortunes by siphoning off public funds, and controlling the lucrative cross-border trade with Iran and Turkmenistan. They cowed the judiciary and appointed their own men to leading positions in the local administration. They enabled and facilitated widespread corruption among the police and security forces. The media across Afghanistan was never fully independent, and freedom of expression was severely restricted, but Shahnaz, like other women and men of her generation, spoke out in the hope of gradually changing the status quo, looking forward to the day when the civil war generation of ageing, corrupt and tyrannical men would be gone.

Shahnaz wasn’t worried when the Taliban offensive began last year. She thought they would capture a few rural districts before being driven out by government forces. It was unimaginable that they would ever come back to Herat, or rule Afghanistan again, because ‘their ideology is so different from what the normal Afghan wants.’ But by early July most of the districts surrounding Herat had fallen. Ismail Khan, the former warlord who led the People’s Resistance Movement in Herat, was captured and paraded on camera surrounded by Taliban fighters. Suddenly the fighters were in the city streets: Shahnaz saw them drive past her house 0n the back of captured Humvees and pickup trucks, brandishing American weapons.

For Shahnaz, the corrupt political elite that she and other activists had fought to expose had enabled the Taliban to come back to power. ‘Yes, we didn’t believe that the Taliban would come, but our people were tired and disappointed with the government. Poverty, corruption and criminality reached a peak under President Ghani. He appointed people to high office he knew were corrupt. People were hungry and poor, but they could see the wealth around them.’ She explained that in Herat corruption among the police and judiciary had led to a rise in crime. The policemen were paid a pittance so they started releasing convicted felons in return for bribes. ‘People were tired of the corruption. Some felt that if the Taliban returned to power they would at least do something to sort out crime. They would execute rapists and amputate the hands of thieves.’

One day during my time in Herat I followed crowds of men heading through the streets to a roundabout in the centre of town where hundreds had already assembled. They had gathered around a truck mounted with a crane. High above them, a corpse hung from the extended arm of the crane. His shalwar trousers were dark with blood, his torso exposed to show two bullet holes in his back. His kameez tunic was wrapped, noose-like, around his head. A piece of paper taped to his chest denounced him as a kidnapper. Some of the men in the crowd were Taliban fighters with guns slung over their shoulders, and they chatted away, celebrating a job well done. But most of the people taking selfies with the hanging corpse were ordinary Heratis. They were here to see the new justice system being implemented in their crime-ridden city.

The legacy of two decades of war can’t be measured just by the number of abandoned airbases and military installations, or by the tens of thousands of Afghans killed. In these years of suicide bombings and insurgencies, night raids and drone attacks, a new generation of Afghan women and men had emerged – but they were trapped between the corrupt elite, the warlords and the insurgents. Now, there seems to be even less chance of breaking free. ‘The Taliban takeover has ruined the lives of hundreds of thousands of young people like me,’ Shahnaz said. ‘Many who spoke out on social media or fought for social justice are in hiding. A whole generation of educated people are leaving, and twenty years of work is being undone. That is how our country is collapsing.’

When I met her, Shahnaz was still teaching, covering her face as the Taliban require, though she hadn’t been paid for months. Parents kept asking her when the Taliban would allow older girls to go back to school. ‘The opportunities we had as women were thanks to our higher education. Think: how can a girl who wants these same opportunities achieve anything if she can only study until the end of primary school?’ Shahnaz believes that the Taliban will use this issue as leverage to force the international community to recognise them, or supply aid. If they soften their stance it will be seen as a sign that they are making accommodations with the West. But the Taliban’s principles are unlikely to change fundamentally. ‘Even if they do let girls back they will impose strict rules and make it very hard for female students to go to university. We lived in a golden age and I thought the next generation would too. If girls don’t have access to higher education how can they become doctors, engineers, lawyers?’

When the Taliban returned to power, there were no sectarian or ethnic massacres, no mass executions. Instead they issued a general amnesty on all military and civilian members of the former regime, and the war ended – almost. Jihadis affiliated with IS are using the Taliban’s old tactics against them: suicide bombers and IEDs. Meanwhile remnants of the Afghan army are mounting sporadic resistance in the mountains of Panjshir. But for the first time in 43 years people aren’t dying every day because of the violence.

When I asked Mawlawi Burjan about the amnesty, and whether men like him or Shir Agha could forgive their opponents and forget about two decades of war, he said that Afghan history was a continuous cycle of violence and that it had to stop. ‘The Taliban have learned that they mustn’t behave as they did in their previous government. That only pushes people to resist and fuels the opposition. Yes, if people, especially in the cities, don’t abide by the Islamic Sharia they should put a stop to it, but by teaching the people not punishing them. The old Taliban were quite brutal. At every checkpoint they would beat people if they didn’t abide by their rules. They would beat women who didn’t wear the burqa, and the men with them, but now you see women showing their faces in the streets.’

The Taliban who entered Kabul last August did behave differently. Gone were the days when they hung computers and TVs from trees, or herded men at gunpoint to perform prayers. Taliban fighters posed for selfies with locals and foreigners, their media wing produced slick videos showing their crack military unit – the Badri – dressed in combat fatigues, carrying American-made guns. If it wasn’t for the white Taliban flags and the occasional curl of long hair escaping from under a helmet, one could easily mistake them for the US-trained special forces of the ancien regime. Some began talking of a Taliban 2.0, a slightly stricter version of the Iranian theocracy, with the leader acquiring a stature similar to that of Iran’s ayatollahs, with a functioning bureaucracy below it. After all, many of the leading members of the Taliban had been living in Pakistan or in Qatar, where their children were exposed to the modern world. In Kabul, the movement’s polite and soft-spoken representative, Zabihullah Mujahid, sought to put a moderate spin on the regime’s pronouncements. He assured the world that girls would be able to receive a full education, though one that adhered to Islamic teachings and Afghan traditions.

Girls’ secondary schools were due to reopen on 23 March, for the beginning of the new academic year. Students turned up, ready for their lessons. But suddenly there was a volte face and the girls were sent home again, thanks to an edict from the Taliban’s central leadership that the opening would be postponed until a ‘comprehensive plan’ could be developed. Other new edicts imposed more restrictions on women, banning them from long-distance travel without a close male relative, ordering them to cover their faces, and removing them from government jobs apart from those in health and education. Some observers speak of divisions between the administration in Kabul, dominated by pragmatic Taliban who want to end their international isolation through diplomatic engagement, and the religious leadership in Kandahar, dominated by the strict clerical jurist Hibatullah Akhundzada, the Taliban’s ultimate authority and Afghanistan’s new de facto head of state.

So is this a new Taliban? The usual answer you hear is perfect double-speak: ‘We are a new Taliban but we are the same Taliban’ – which seemed to mean nothing until I met a young official in the Taliban’s Ministry of Information who tried to explain it to me. ‘The Taliban is the same Taliban with the same goals and ambitions,’ he said. ‘From the beginning our goal was, and still is, to establish an Islamic state.’ The difference is that the tools the first Taliban government used to spread their message were crude and unsophisticated. ‘Back then we were at war all the time, and all our important leaders were engaged in fighting. We didn’t pay attention to the media, and our opponents controlled the narrative, and distorted our image in the eyes of the world. Now we have our own media, and we are spreading our rules of Islamic laws through these outlets.’

The official had been a university student when the last Taliban government came to an end. He said he decided to join the movement at the moment of its defeat, when he saw the bombs falling on the hills outside Kabul. He joined the remnants in the east and then crossed with them to Pakistan. There he opened a shop selling mobile phones and he and a friend taught themselves to code, building websites to spread the Taliban message. ‘At first we were using simple websites – there was no Facebook or Twitter then. I worked with IT people from Iran and Pakistan, bought servers in places like India and Canada, and uploaded poems and sermons.’ Then came the rise of social media, and he and his small team opened multiple accounts on the various platforms, using them to broadcast news and share jihadi videos. ‘We had some security issues on Facebook sometimes, but we had no problem with Twitter. And I still have my Twitter account.’

‘I am proud of one thing,’ he said. ‘I never took any courses or went to IT school. I learned everything from Google. Yes, our opponents had better technology. But we had the grace of Allah and we defeated American, Turkish and Indian hackers.’

The Taliban inherited an economic catastrophe, which has been getting worse, largely because of the country’s current pariah status. The US-imposed asset freeze has crippled the administration, preventing it from paying salaries, forcing public sector employees – already paid a pittance – into debt and denying them the ability to help their relatives in the countryside. In Kandahar, women in faded burqas sit by the side of the road and jump to their feet whenever they see a pickup truck go by carrying Taliban. The women run after the trucks, hoping they’re distributing food aid. Men, too, queue up for Taliban charity, most of them former sharecroppers driven from their lands by drought and war.

In Kandahar’s main hospital, a doctor told me that the number of children suffering from acute malnutrition has more than doubled over the past year. ‘We feed them, they get slightly better, their mothers take them back to their villages and a couple of weeks later they are back.’ He said the mothers are given food packs for their children, but it’s never enough, because they have no choice but to share the rations among all their children, sick and healthy. Three and sometimes four children occupy each hospital bed, tiny skeletons with exposed ribs and inflated stomachs. There is little difference in size between five-year-olds from Panjwayi district outside Kandahar and two-year-olds from Helmand. The numbers are horrific: Unicef estimates that two million Afghan children require treatment for acute malnutrition. In a country where 97 per cent of the population lives below the poverty line, this is a crisis that is not going to be easily resolved.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.