Nevertheless, The North Fork Holston River Has Persisted

By Molly Kirk/DWR

To see the sparkling, clear waters of the North Fork Holston River meander through the foothills of the Clinch Mountains in Southwest Virginia, you’d never know that the beautiful 138-mile stretch of water has endured one manmade disaster after another. The North Fork Holston winds through the Rich Valley from Sharon Springs in Bland County, Virginia, to Kingsport, Tennessee, where it joins the South Fork to form the Holston River, which ends at the Tennessee River in Knoxville. Its waters are home to a thriving smallmouth bass fishery along with multiple imperiled mussel and fish species.

“It’s a beautiful mountain stream. If you were there today, you’d never imagine what humans have done to that valley,” said Tim Lane, Southwest Virginia mussel recovery coordinator for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR).

“As a tributary of the Holston and part of the Tennessee River drainage, which has an incredibly biodiverse population of fish and freshwater mussel species, the North Fork Holston is a pretty unique waterbody,” said Mike Pinder, DWR’s nongame fish biologist. “The area is remarkable for its natural and cultural history. I hope that people appreciate what it has to offer.”

A Turbulent History

The North Fork Holston has been defined and shaped for the last two centuries by what humans could extract from the land around it. Saltville, a town located midway between the North Holston’s source in Bland County and where it crosses the state line in Scott County, is named for the area’s most distinctive feature, the Saltville Well Fields. The only inland saline marshes in Virginia, these wetlands have been valuable for many generations for many different reasons.

The remnants of an ancient sea underground, which seeps through layers of limestone and dolomite, brings brackish waters to the surface, where evaporation forms rock salt. Around the edges of the brackish lakes and marshes, encrusted salt could be found. Fossils indicate that ice age mammals, including mastodons and giant sloths, visited these natural salt licks.

“The salt resources have attracted both wildlife and people to the area for a millennium,” Pinder said. Bison were frequent visitors to ingest the mineral, and Native Americans used the salt to preserve meat. In the 1700s and 1800s, after colonials had settled in the area, wells were dug to access the briny water and manufacture salt. During the Civil War, Saltville was known as the “Salt Capital of the Confederacy” and battles were fought for control of the salt fields, since the mineral was essential for both sides.

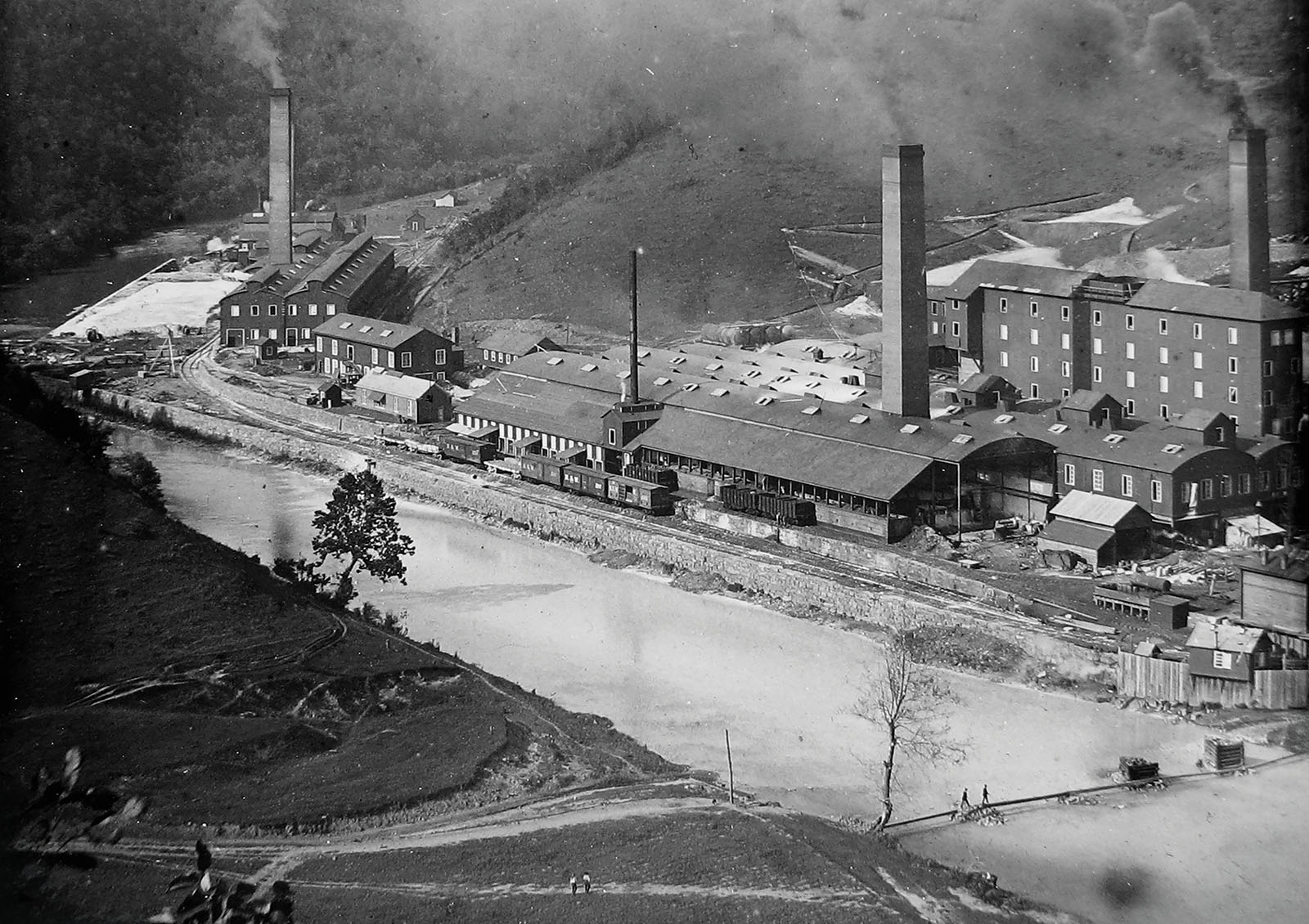

By the late 19th century, the railroad reached Saltville, accelerating the industrialization of the area. Mathieson Alkali Works set up shop, using the salt pumped from the ground to produce bicarbonate of soda. The company grew, becoming Mathieson Chemical Corporation in 1848 and expanding to produce soda ash and caustic soda, building blocks of multiple consumer products and chemical compounds.

The Mathieson Chemical Corporation on the banks of the North Fork Holston River in the late 19th century. Photo courtesy of the Museum of the Middle Appalachians

Over the decades, the Mathieson company became the lifeblood of Saltville’s population and economy. But their processes also resulted in mass quantities of alkaline byproducts. These were collected in a “muck lake” on the banks of the river. On December 24, 1924, the dam holding that caustic mess failed, releasing a huge mudslide of toxic byproduct into the North Fork and onto Palmerton, a small village half a mile from Saltville.

In his book “A History of Saltville,” William B. Kent described it as “a wave of muck nearly a hundred feet high and over three hundred feet wide swept into the river and over a hill and through the village, sweeping houses, barns, trees, and everything in its path, or else burying them to a great depth under its white slime. So great was the force of the bursting of the dam, backed up as it was by around thirty acres of muck and water, that great boulders weighing fifteen to twenty tons were hurled across the river and over the hill on the opposite side, a distance of over two hundred and fifty yards.” The community was devasted, with at least 19 people dying and massive property loss.

The effects on the river itself were also catastrophic. The large influx of toxic alkaline byproduct resulted in a massive fish kill, with newspaper accounts describing thousands of fish floating in the waters downstream of Saltville.

In 1947, another calamity befell the North Fork Holston when a gypsum mine shaft that had been dug under the river three miles upstream from Saltville collapsed, diverting the entirety of the river’s waters into the abandoned mine and underground caverns for 48 hours.

Nevertheless, the Saltville area rebounded, and the Mathieson Chemical Corporation kept operating, creating more and more toxic byproduct, which they deposited into pools alongside the river. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), those pools seeped contaminants, including mercury, into the groundwater and the North Fork Holston River. In 1970, as a result of mercury concentrations found in fish, both Virginia and Tennessee placed fishing in the river under a health advisory. The Virginia Department of Health has also issued a “Do Not Eat” fish consumption advisory from Saltville approximately 84 river miles downstream to the Virginia/Tennessee border. That do-not-eat advisory is still in place.

Local resident Cecil Malcolm grew up south of Saltville in Mendota, and he has memories of catching big smallmouth out of the North Fork Holston below Saltville. “But every once in a while, they would turn the alkali loose,” he said. “And when it did, it just killed everything down the river. There would be fish floating all over that river.” In the early 1970s, the North Fork Holston was rated as one of the most polluted rivers in the United States.

By 1972, the company—now the Olin Mathieson Corp.—shut down their business in Saltville in response to improved water quality standards. The town prevailed, developing other industries, but the river’s waters below Saltville still bear the scars of the ravaging pollution of decades.

Bringing the Yellowfin Madtom Home

“The water quality south of Saltville definitely got impacted, but there are some positive signs that show that there’s some recovery going on,” said Pinder. “I’ve seen an Incredible diversity of fish species such as darters and minnows especially north of Saltville. The valley is mostly agricultural, and the ridges are forested, so the water is typically very clear during low flows.”

Despite the number of toxins that cause the do-not-eat advisory, the North Holston’s waters south of Saltville support a thriving catch-and-release smallmouth bass fishery that delights anglers. “It’s no-consumption in the area, but the game fish have largely recovered,” said Jeff Williams, DWR district fisheries biologist. “As far as our smallmouth bass fishery, it’s one of our best smaller rivers down here in the region. There are also strong rock bass, red breast sunfish, and channel catfish populations.”

Sampling by DWR shows that the North Fork Holston south of Saltville hosts healthy smallmouth bass populations. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

And the waters north of Saltville have become a haven for imperiled species native to the Tennessee River drainage, such as yellowfin madtoms, Tennessee bean mussels, eastern hellbender, and multiple species of crayfish.

Pinder’s focus has been on restoring the populations of yellowfin madtoms (Noturus flavipinnis), a charming three-inch catfish, to the North Fork Holston. The species, found only in the Tennessee River drainage, was listed as threatened on the Federal Endangered Species List in 1977. Reports from the late 19th century state they were once common in the North Fork Holston, but they disappeared from its waters likely due to water pollution and introduced species.

DWR and partners have worked to re-introduce the yellowfin madtom into the North Fork Holston River. Photo by Maddie Cogar/DWR

In 2016, DWR collaborated with Conservation Fisheries, Inc. (CFI), a nonprofit organization in Knoxville, Tennessee dedicated to the preservation of aquatic biodiversity, to release juvenile yellowfin madtom into the North Fork Holston. Local schoolchildren helped place fish in the water on the release day. With the help of local landowners, these efforts have continued for the last nine years.

“It’s interesting, because the North Fork Holston is where the yellowfin madtom was first discovered back in 1888, so in a way it’s a homecoming for the species,” Pinder said. “The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service provides the funding, while CFI propagates them and helps us monitor the new population.” None of this would be possible without the work of conservation groups and landowners that continue to help improve water quality.

Mike Pinder, DWR nongame fish biologist, holds a bag of juvenile yellowfin madtoms that were propagated by Conservation Fisheries Inc. and then released into the North Fork Holston River. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

A Rich Diversity

Another fish federally listed as threatened, the spotfin chub (Erimonax monachus) actually swims throughout the waters below Saltville. “That’s where worst impacts occurred, so either they were able to find refuge in tributaries or recolonize naturally from further downriver,” Pinder said. “We’ve been contracting CFI to monitor them for the last six years, and the population seems to be doing quite well. So, that’s a positive sign.”

Two male spotfin chubs. Photo by Mike Pinder/DWR

In the 1980s and ’90s, spiny river snails (Io fluvialis) were reintroduced into the North Fork Holston and are now thriving as well. And multiple species of crayfish—including the longnose crayfish (Cambarus longirostris), angled crayfish (Cambarus angularis), and reticulate crayfish (Faxonius erichsonianus)—inhabit the river bottom and are a critical thread of the aquatic food web.

The Tennessee River drainage system is famous for its diversity of freshwater mussels, and Lane notes that 19th century records indicate that 30 species of freshwater mussels once populated the North Fork Holston. “Out of the 30 that should be there, there are 13 mussel species in the North Fork Holston,” Lane said. In 2022 and 2023, DWR placed about 500 Tennessee bean mussels in four locations near Broadford, northeast of Saltville.

“After [Pinder] was having success getting yellowfin madtoms reestablished, we decided that that was an appropriate place to reintroduce some mussels. We’ve been monitoring those animals, and they’re doing really well. We’ve found 60 percent of them alive the last couple of years,” Lane said. He’s hoping to possibly reintroduce some other imperiled mussel species to the upper reaches of the North Fork Holston.

“There are five to 10 species that we could probably make the argument would be good to put back in there,” Lane said. “It may never support the huge, abundant numbers that would have been downstream, but at least there would be some redundancy for an endangered species, another dot on the map where they exist.”

Another unique species present above Saltville is the eastern hellbender, Virginia’s largest aquatic salamander. “DWR’s long-term collaborative research with Virginia Tech has shown that hellbenders still occur above Saltville and some even produce fertilized eggs, which provides hope that they can recover with a little bit of assistance,” said William Hopkins, Wildlife Conservation Professor at Virginia Tech. Plans to help the “snot otter” involve “using the existing populations as the genetic stock for headstarting baby hellbenders to accelerate their population recovery in the North Fork Holston. Combining these efforts with habitat restoration and best land management practices might make it possible for these incredible animals to once again have self-sustaining populations,” Hopkins said.

An Underrated Gem for Recreation

Pinder describes the North Holston as “an overlooked treasure” for outdoor enthusiasts. “It still has some healing to do, but people can enjoy it,” he said. “There are a lot of things that make it a treasured resource.”

“It’s not a big river like the New or the James, but for the system of its size, it produces some really good smallmouth bass,” Williams said. “It’s a great resource, and we definitely want folks to take advantage of it. We at DWR will do our part to continue to manage the fishery and try to get additional access when it’s practical.”

But both noted that lack of public access to the river’s waters does limit its public use. Malcolm, who has now owned a farm on the North Fork Holston upstream of Saltville for more than 25 years, allows DWR and conservation groups to access the river from his land, and he’s tried to spread the word to other residents about conservation and water quality improvement efforts. “When I first came up here, I didn’t want to leave,” Malcolm said. “It’s just a quiet, peaceful place and a beautiful river.”

Local landowners like Cecil Malcolm (right) and his wife, Billie, have been essential pieces in the puzzle of North Fork Holston River restoration. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

“It’s obvious that Mr. Malcolm treasures this amazing site,” Pinder said. “He was really excited when we showed him all the freshwater mussels and fish that live in the river on his property. He knows so much of the history of this river, and he has so much appreciation for what it brings him.”

To bring more attention to the region’s incredible natural beauty and recreational opportunities, the Mendota Trail Conservancy imagined and put into place a rail trail, the Mendota Trail, which stretches 12.5 miles between Bristol and Mendota, following the former railroad line on the south end of the river. Bill Tindall, a founding conservancy member, was instrumental in its construction and management. However, the trail almost failed before it was started when it came to the cost of restoring the 273-foot-long bridge crossing the North Fork.

“It was pretty clear that this trail was stalled until that happened. So, my wife and I talked about it, and we decided that we would pay for restoring the bridge over the Holston River,” said Tindall. The newly restored bridge was named the Sunnyside, in honor of “Keep on the Sunny Side,” a theme song of the Carter Family, the first family of country music, whose members grew up nearby in the valley. Now owned and managed by Washington County, the trail incorporates 17 trestle crossings of creeks and the North Fork Holston and has become popular with hikers and cyclists.

“The North Fork Holston had this incredible diversity, but it got hammered by contamination. Nowadays, it gets overlooked quite a bit because of this past history,” Pinder said. “But there is hope that the system is recovering, especially with the conservation efforts around the mussels and the fish. The North Fork is a hidden gem, and it has such a neat story.”

Molly Kirk is the DWR creative content manager.

Distribution channels:

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release